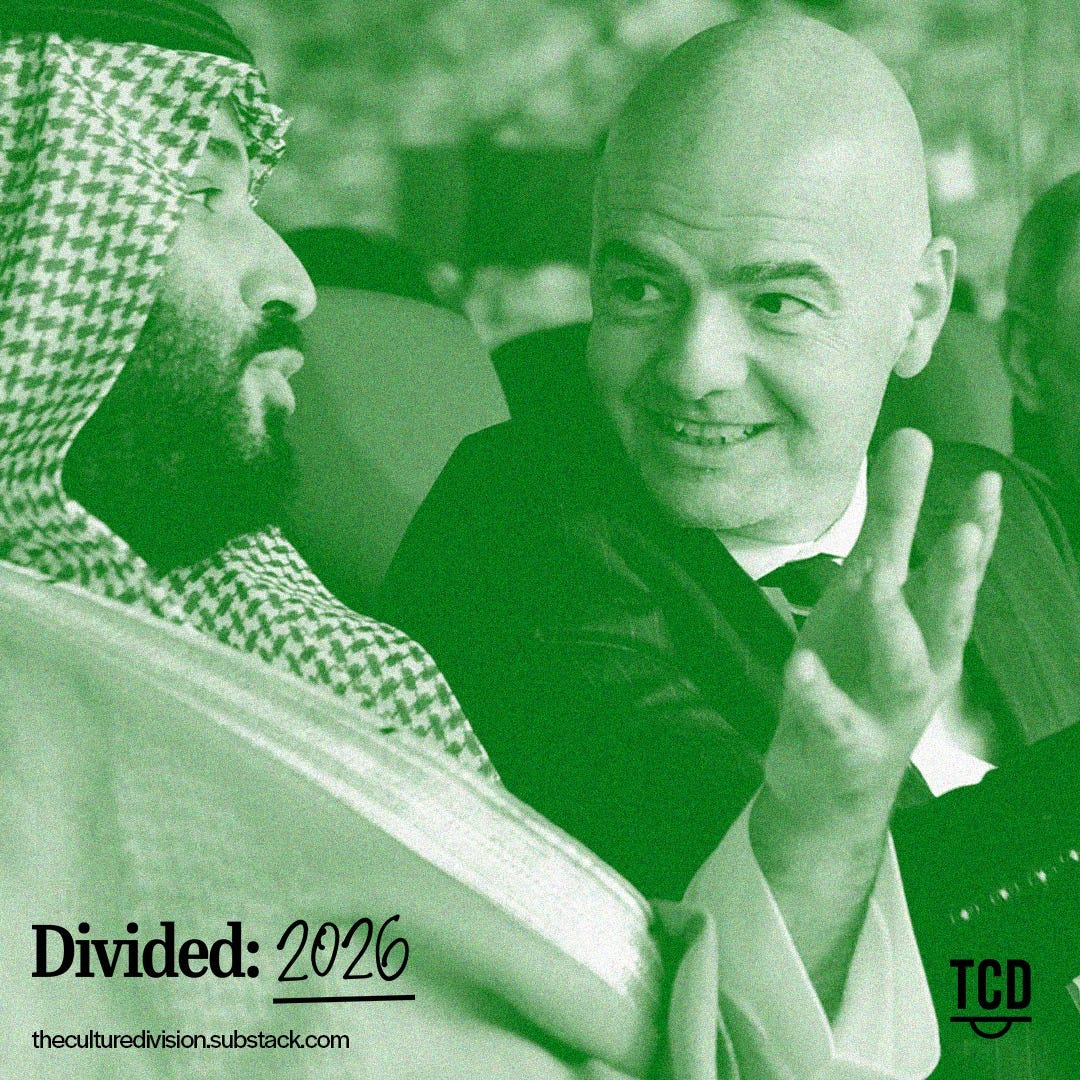

Infantino’s Saudi love-in is harming the game

State-level ownership of the game is now completely normalised. But Infantino's Saudi obsession represents something far more worrying

Arriving two hours, 17 minutes late to last month’s annual FIFA Congress in Asunción, Paraguay, Gianni Infantino made sure to put on a brave face. The same smiling, slightly glib, brave face that unveiled the expansion of the World Cup, or the awarding of the 2034 edition to Saudi Arabia, or that defended Qatar’s treatment of migrant workers in 2022.

But this was an overstep. Late to his own party. His private jet was delayed leaving the Gulf, where he’d spent the previous days schmoozing with Donald Trump, Mohammed bin Salman, and other US and Middle Eastern leaders.

In an explosive statement, UEFA argued the delay in schedule was “simply to accommodate private personal interests.” Several members of European football’s governing body, including president Aleksander Ceferin and FA chair Debbie Hewitt, staged an unprecedented walkout, citing the need “to make a point that the game comes first.” The empty seats were a powerful image; a symbol of the fractures that lie within the FIFA – fractures that Infantino’s leadership has done nothing to alleviate.

“I felt I needed to be there to represent football, and all of you,” said Infantino, in his hurried and apologetic address to the Congress.

Just a few days earlier, Infantino spoke at the Saudi-US Investment Forum in Riyadh, doing what he does best: marketing the beautiful game to a room full of suits. “Invest in the beautiful game,” was his call to action. “It will be the best investment you can make!” He talked about the global football economy, making the case that a little more Saudi or US investment could well tip football’s GDP to surpass half a trillion dollars.

Buy, buy, buy. Sell, sell, sell.

Infantino’s relationship with the Saudi government and Mohammed bin Salman in particular is longstanding. The pair shared a box together at the opening ceremony of the 2022 Qatar World Cup. Just three months later, FIFA selected Saudi Arabia to host the 2023 Club World Cup.

In April 2024, FIFA announced a four-year sponsorship deal with Aramco, the Saudi state-owned oil and chemicals company – including major rights to both the 2026 World Cup and the 2027 Women’s World Cup. Valued around $100 million annually, it is one of the most lucrative sponsorship deals in the history of the sport. In October of last year, over 100 female players called for FIFA to end the partnership, citing a misalignment of values with respect to “gender equality, human rights and the safe future of our planet.”

Just last year, in an almost intentionally muted virtual ceremony, Saudi Arabia was awarded – without contest – the hosting rights of the 2034 World Cup. It was a processional rubber-stamp. FIFA’s own evaluation of the bid recorded, miraculously, the highest score ever. Only two of the proposed stadiums currently exist.

“What Saudi Arabia has put forward in their bid is absolutely incredible,” Infantino said.

In the wake of the decision, human rights organisation FairSquare said: “It is evident that without urgent action and comprehensive reforms, the 2034 World Cup will be tarnished by repression, discrimination and exploitation on a massive scale.”

Last month, a group of leading lawyers, including FIFA’s former anti-corruption advisor Mark Pieth, submitted a 30-page official complaint – arguing that Saudi Arabia’s hosting of the 2034 World Cup sits in contravention of FIFA’s own human rights policies. It points to five key areas: freedom of expression and association; the rights of migrants; the rights of women; mistreatment and the death penalty; and judicial independence.

Just last week, trade unions from 36 countries filed a complaint with the UN’s International Labour Organisation, calling for an inquiry into the conditions of migrant workers in Saudi Arabia. “We cannot remain silent while migrant workers, especially construction and domestic workers, continue to face fundamental rights violations,” said Luc Triangle, general secretary of the International Trade Union Confederation.

And on the eve of the inaugural Club World Cup, FIFA unveiled that PIF, the Saudi Public Investment Fund, would be joining the tournament as an official partner. That PIF is the majority shareholder of Al-Hilal, who will earn circa 10 million dollars for taking part in the tournament, was absent from the press release.

Saudi investment in football is not a steady mission-creep, it’s a calculated geopolitical strategy that has permeated a number of sports; the Kingdom’s influence on golf, boxing and Formula One, for example, has become completely normalised. Western institutions, sporting or otherwise, are only too happy to accept what is ostensibly free money.

In December 2024, FIFA revealed that loss-making broadcaster DAZN had purchased the rights to show this summer’s Club World Cup matches, for free, on their streaming platform. They paid a reported $1 billion for the privilege.

In February of this year, Surj Sports, the sports investment arm of the Saudi sovereign wealth fund, purchased a minority stake in DAZN. The price for their investment: $1 billion.

Imagine the surprise, then, when less than a month later, in an attempt to drum-up interest for what had largely been viewed as an inconvenience (particularly by the big-draw European clubs), Infantino proudly announced a staggering $1 billion prize fund for participants of the Club World Cup. He wore the same, slightly glib, brave face.

This is Infantino’s FIFA. His relentless courting of the world’s most powerful leaders has created a revolving door of petro-state investment, inflated sponsorship deals and hefty prize pots. For Infantino, it is necessary to be at Gulf investment summits, to travel by private jet, to discuss things like “global GDP”. He is an important man.

But as those who walked out of the Congress in Asunción pointed out, his job is to serve the federations that elected him. He is supposed to act in their interest. His deference to the interests of Saudi Arabia, the United States, and his endless obsession with image curation, has allowed a great selling-off of the game’s legacies and assets – and perhaps its soul.

His mission in these circles might well be to “represent football.” But no-one seems to have asked whether that’s a good thing.

wasn’t he supposed to clean up fifa after sepp blatter ? 😂